scroll down for English

Dunque, come scrivevo, questo infinito sgomento – non

della morte, affatto- le grandi ali dei suoni.

Giovanni, si era arrampicato

su una roccia strappando un ramoscello pieno di belle bacche.

Le ha date alla Gemma. Oh! – disse- Io stavo a guardare tutto.

Ancora una volta mi metto a immaginare quel fatto

ma di quanti anni prima? dopo quanti anni?…

MATERNITA’

prima

Io le sentivo allora dalla spaccatura, intanto di soppiatto

…..fissavo

le loro garze inzuppate e gli stracci

buttati nel catino, su cui sfolgorava lucentissima la luce

…..del sole

dal vetro della finestrella; – e mi sentivo così solo e sopraffatto

come se in quel momento mi fosse stato dato a sorte

il miracolo stupefacente della vita. Avevo anche

…..timore

che la balia uscisse all’improvviso e mi trovasse dietro

…..la spaccatura

a sbirciare quell’evento a me proibito – soprattutto

scoprisse che avevo sentito le loro parole, scoprisse

la mia bravata maldestra.

segùnda

Dopo l’ultimo parto era smagrita;

le palpebre sempre inarcate; i seni

avevano perso la forma – lei lo vedeva e lo nascondeva

…..e era smarrita, silenziosa,

quasi per conto suo.

…..A volte, invece, si sedeva

immutabile, per attimi e attimi,

nella stessa posa, e assorta,

nel piccolo sgabello di betulla; si passava le mani

con un pezzo di sapone sbeccato – io lo intuivo

dall’odore entrando in stanza sua –

e mi piaceva, perché il sapone era sempre destinato

al giorno della festa e della domenica; – e ancora, adoperava

varie erbe officinali, raccolte di fretta la sera al scendere del sole,

erbe che rinfrescavano la pelle e davano alla faccia un carnato

lucido e pallido. Un giorno

mi guardò che la guardavo nello specchietto

forse aveva sentito la mia presenza alle spalle,

e sobbalzò tutta: fece una mossa

come se fosse scesa di colpo da un salto.

“ Così, hai notato anche tu che sono sciupata?”

e all’istante ridivenne lieta, consolata, bella

come un tempo, prima del suo mutamento

e prima dei grandi mutamenti incontrollabili del tempo.

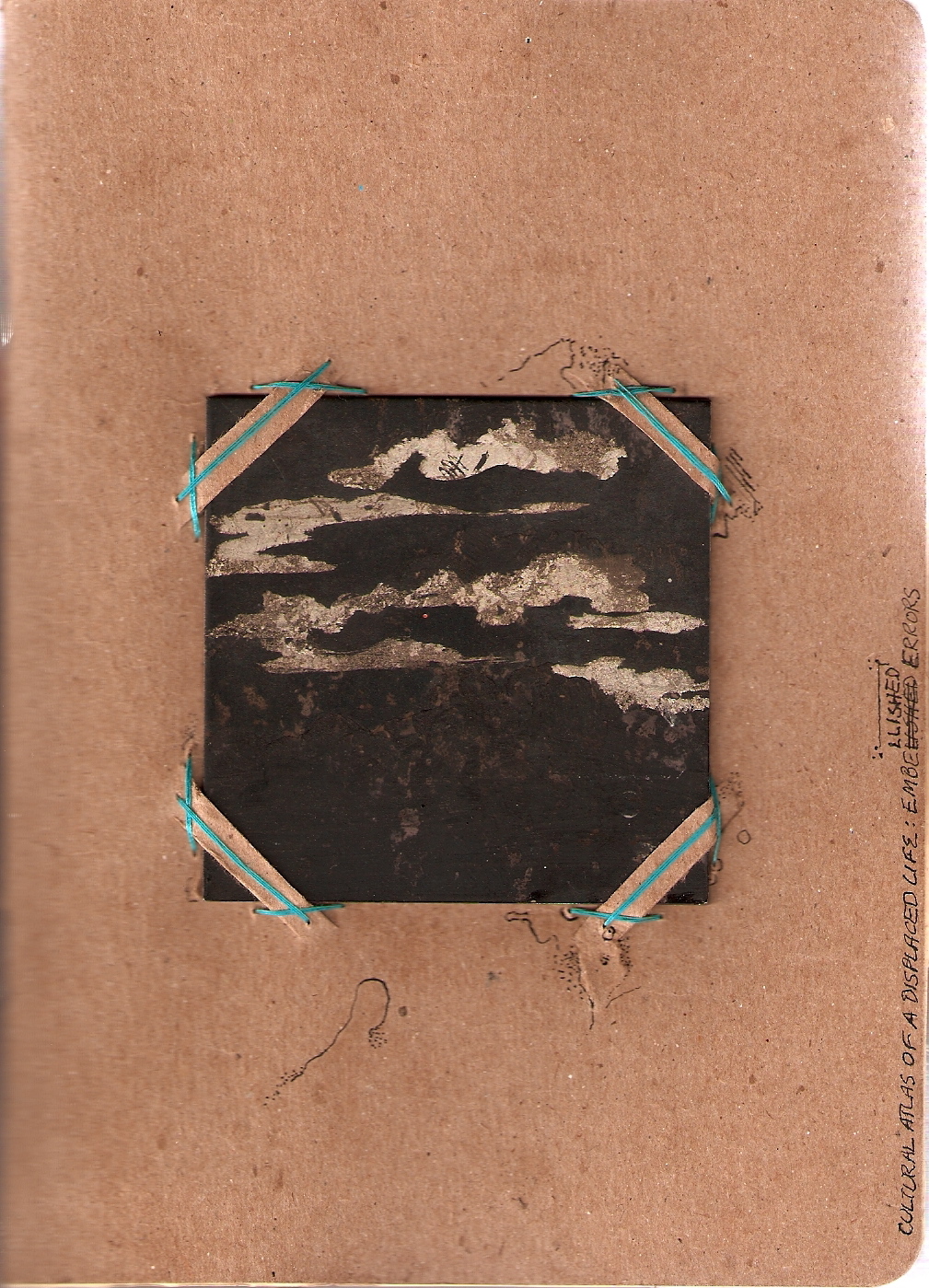

“Una camminata fatto in quei

giorni che il freddo accorcia la pioggia… io

e lei, la Gemma, mia madre, di 95 anni”.

tèersa

Portami a camminare con te

appena lì avanti, fino al muro della contrada,

fin dove la valle si apre e appare

il campanile peraria e di sasso, calcinato dallo sprazzo

…..di luna,

così peraria e immateriale

così distaccato, quasi etereo

che puoi anche credere che non esiste

il vuoto con le sue lontananze.

Portami a camminare con te.

Ci abbandoneremo un momento sul sasso,

sul dosso,

e inumidendoci fra serti di brina

forse crederemo persino di volare,

perché a volte, come adesso, sento lo stropiccìo

…..dei miei panni

che sembra il fremito di due ali grandi,

e quando ti accosti a questo battito del volo

senti alleggerirsi le braccia, il corpo, la tua figura,

e così avvolto nella cornice di una brina azzurra,

negli tratti liberi dell’anima

non ha importanza che tu salpa o ritorni,

né importa che i nostri capelli siano imbiancati,

(è questo che mi dà tenerezza – e mi dà tenerezza

che s’imbianca anche lo sterrato).

Portami a camminare con te.

peraria: cavato su dal dialetto vecchio

Trovate QUI più informazioni su Giacomo Gusmeroli, il suo ultimo libro, “Quattro mesi e venti giorni” è uscito per LietoColle.

* * * * *

An English translation of this poem can be found below:

So, as I wrote, this infinite dismay – not

of death, at all – the broad wings of sounds.

Giovanni, had climbed

up on a rock tearing off a small twig full of beautiful berries.

He gave them to Gemma. Oh! –she said– I was watching everything.

Once again I re-immagine that moment

but how many years before? after how many years?…

MATERNITY

first

I could hear her then through the fissure, meanwhile furtively

…..I stared at

their sopping gauze and the rags

thrown into the basin, on which the polished sunlight

…..blazed

from the window’s glass; – and I felt so alone and overwhelmed

as if in that moment I had been given at random

the stupefying miracle of life. I was also

…..afraid

that the nurse would come out suddenly and find me behind

…..the fissure

peering in at that event forbidden to me – especially

discover that I had heard their words, discover

my clumsy escapade.

second

After the last birth she was gaunt;

eyelids always sagging; her breasts

had lost their shape – she saw it and hid it

…..she was lost, silent,

almost of her own accord.

…..Sometimes, instead, she would sit

unchangeable, for moments and moments,

in the same position, and lost in thought,

on the small birch stool; she passed a chipped

bar of soap over her hands – I intuited that

from the smell upon entering her room –

and it pleased me, because soap was always used

on holidays and Sundays; – and still, she employed

various medicinal herbs, quickly gathered in the evening when the sun went down,

herbs that refreshed the skin and gave the face a pale and glowing

flesh. One day

she saw that I saw her looking in the mirror

perhaps she felt my presence at her shoulder,

and she started: with a movement

as if suddenly landing hard from a jump.

“So, have you also noticed that I’m falling apart?”

and instantly she became happy again, consoled, beautiful

as she once was, before her change

and before the great, uncontrollable changes of time.

“A walk taken in those

days when the cold cut short the rain… She

and I, Gemma, my mother, 95 years old”.

third

Take me walking with you

just there ahead, up to the wall of the contrada,

up to where the valley opens up and it appears

the unearthly bell tower of stone, whitewashed by the flash

…..of moonlight,

so unearthly and immaterial

so detached, almost ethereal

that you can even believe it doesn’t exist

the void with its remoteness.

Take me walking with you.

We let ourselves go for a moment on the rock,

…..on our backs,

and dampened among garlands of hoarfrost

perhaps we believe we can even fly

because sometimes, like right now, I hear the rustling

…..of my clothes

that seems like the flapping of two broad wings,

and when this beat of flight accosts you

you feel your arms, your body, your features, lighten

and so wrapped up in the frame of azure hoarfrost,

in the liberated lines of the soul

it doesn’t matter if you’re taking off or returning,

nor does it matter that our hair has turned white,

(it’s this that moves me – and it moves me

to see that the path has also turned white).

Take me walking with you.

(translated by Bonnie McClellan)

for more poems by Giacomo Gusmeroli on this blog, click HERE.

LE PRIME ORE D’UN POMERIGGIO

LE PRIME ORE D’UN POMERIGGIO