This is neither a beginning

nor the prophecy of an ending

for beginnings & endings are lies

told to the once-living

it is not the exemplifying

of the aberrations the alchemists made

when they dethroned our Divine Queen

& transmuted her golden honey

into their iron pyrite philosophy

that left us to wither

inside our stunned husks

& so this is the emptying

of our errant devotion

to the denial of bodily hunger

the sanctified unbelieving

in fairytales of heavenly salvation

& it is the vital refilling

of infants’ gaping mouths

with earthly fortitude

& here now is the weeping

for our birth-story interred

with our long-dead mothers

who delivered us

& secured our velvety aboriginal flesh

to their warm breasts—

the saline unleashing

to purify our Logos

our will to creation our innate need

to manifest our god-selves

it is the recovering

of the Life that was severed from our psyches

when it was reduced to a Word

& uttered bereft of melody—

the unrepressed singing

Artemis awake from her slumber

beneath her ruined Temple in Ephesus

at last this is the extricating

of shame that made our tongues

untie us from our Mother’s holy earth

& swayed our ears to scorn her winged songs

even as she kept flying back to us

ever thick-limbed & fragrant

with nourishment from lavender blooms

solely that we should swell in our birthing cells

gorged on her royal jelly

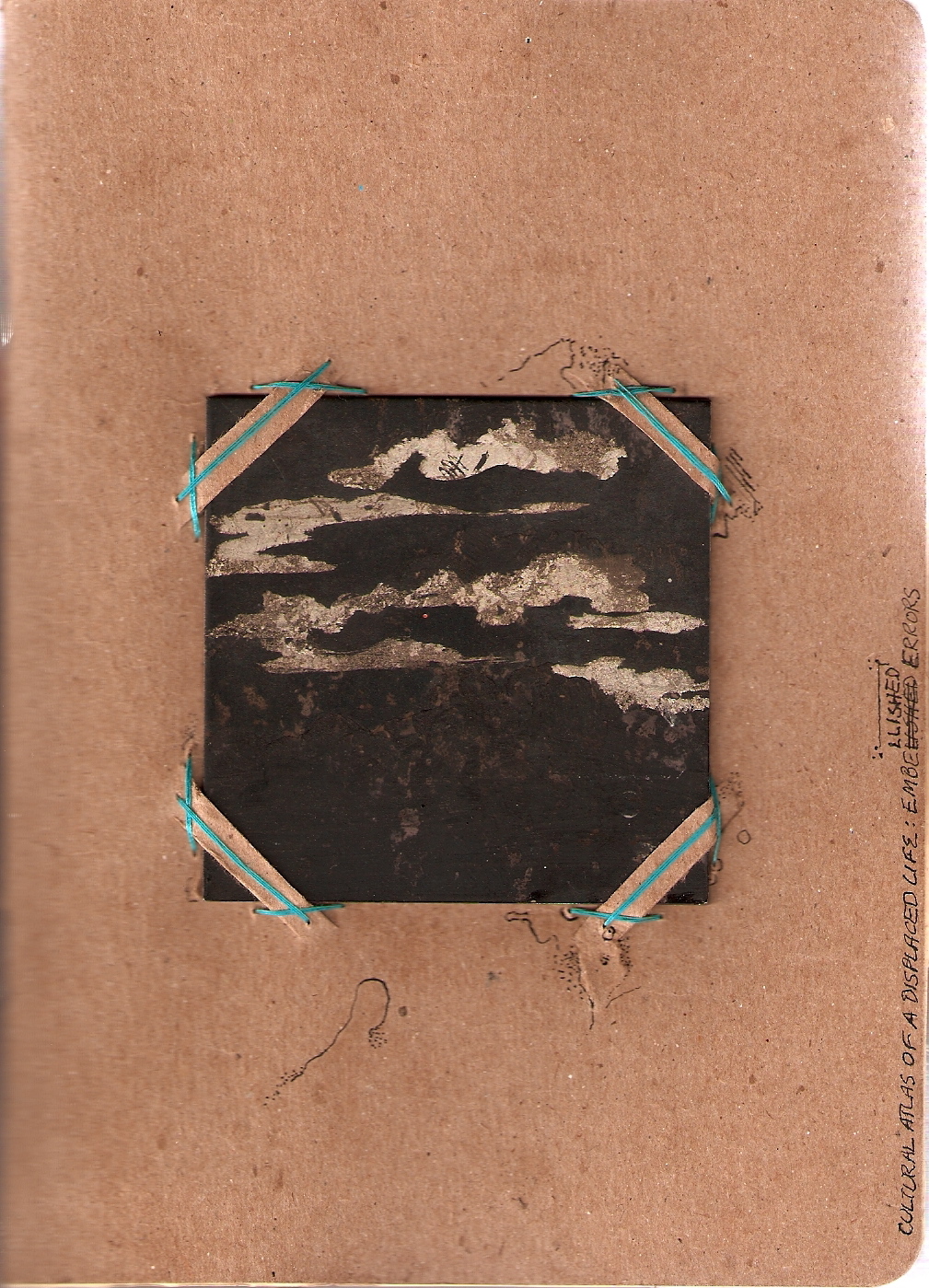

This poem is my body

embryonic translucent

distended with new hope

it is my luminous black eyes

grown huge with their memory

of who I am

To listen to a reading of this poem, click on the player below:

You can read more of Stephanie L. Harper’s poetry on her blog, HERE.